(Nie)uchronność Baby, UAM Poznań 2016

Malarstwo Krystyny Lipki-Czajkowskiej jest nienachalne, dalekie od megalomanii, ekshibicjonizmu, dosłowności, iluzji oraz mody. Autorka przepisuje obrazy z oryginałów, które, jak sama mówi, w niej „siedzą”. Jest malarką, która buduje swoją relację z dziełem w trakcie jego kreacji i później, gdy utrwalone zostanie na płótnie, a niekiedy nawet na tipsach. Autorka „lubi, gdy obraz ją zaskoczy”, gdy „obraz ją poprowadzi”, gdy „się od niej oddzieli”, a wreszcie – gdy „da jej spokój”. Malarka traktuje swoje obrazy jak medium, które łączy nas z prawdą o jej kobiecości, niekiedy nawet „kobietości”, z rzeczywistością daimoniczną, z geometrią duszy i ciała, z przestrzenią jej intymności i z intymnością jej przestrzeni. Malarka zawsze czeka na moment, gdy obraz „oddziela” się od niej, wtedy na chwilę życie staje się wieczne.

Napisałem, że malowanie Artystki jest przepisywaniem wewnętrznych oryginałów zdeponowanych w niej przez codzienność, sztukę, opowieści babki, kulturę, macierzyństwo, seksualność, kobiecość, wrażliwość, cielesność, wreszcie przez daimoniony. Przepisywanie jest właściwe sztuce religijnej. Moim zdaniem wiele jest z tradycji ikonopisania w tym, jak Malarka przedstawia obiekt postrzegany jednocześnie z różnych punktów widzenia na płaszczyźnie, jak odwraca perspektywę malarską, jak układa kolory i wartościuje je symbolicznie, jak buduje hierarchie ważności postaci i rzeczy. To nie są proste inspiracje wynikające z treści. To nawet nie są inspiracje. To są ramy interpretacyjne, za pomocą których można wejść w jej malarstwo i w jej cielesność trawioną przez czas. Malarstwo Krystyny Lipki-Czajkowskiej jest ikonopisaniem codzienności, w której kobiecość pełni funkcję sacrum rozpadającego się na profanum spraw, zadań, obowiązków, ról, funkcji, mód, potrzeb, cudzych oczekiwań. Ten rozpad jest potrzebny, aby zrodziła się w kobiecie Baba. Jest taka historia z jej życia, która potwierdza powyższą intuicję. Rozmowa telefoniczna, jakich wiele w życiu każdego z nas. Ktoś pyta: „Malujesz sobie? To zadzwonię, jak ci wyschną… a na jaki kolor?”. „Niebieski.” – odpowiada Malarka. „Niebieski?” – dziwi się ten ktoś. Wiadomo: skoro dom, skoro rodzina, skoro dzieci, to nie może być już miejsca na nic innego, jak tylko na malowanie paznokci. Dużo wynika z tej rozmowy. Po pierwsze, że narzucając kobiecie typowe role społeczne tłumi się jej pragnienie emancypacji. Po drugie, że zazwyczaj nie oczekuje się wielowymiarowości od kobiety, gdy realizuje ona oczywiste zadania, wtedy wycinek jej osobowości musi wystarczyć za całość.

Przyznać trzeba, że Artystka przenosi niektóre swoje obrazy na tipsy, mierząc się z ich sztucznością, pozornością trwania, a także z tym wszystkim w kulturze współczesnej, czego one są znakami. Malowanie tipsów może stać się działaniem twórczym, wszak, jak mówi sama Autorka: „Malowanie jest kobiece.”

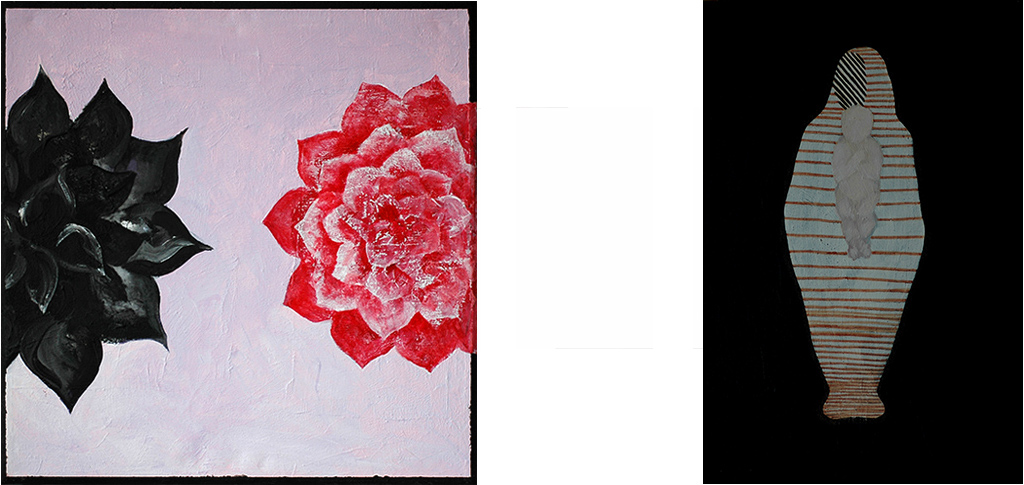

W kulturze europejskiej ciało kobiety od wieków jest przedmiotem adoracji, uwielbienia oraz potępienia. Kobieta jest życiem, jest też śmiercią, gdyż jej ciało staje się pomostem między naszym niebyciem i byciem; rodzimy się z niej i dlatego później umieramy. Ciało kobiety jest kołem, w którym zamknięty jest czas ludzkiej egzystencji. Może dlatego tysiące lat temu znajdowano, jak pisze Karl S. Guthke w książce The Gender of Death, podobieństwa między ciałem kobiety i ziemią, która daje życie – wprowadzając je w porządek śmierci. Już Wenus z Willendorfu obrazuje tę zależność – kobieta jak ziemia jest płodna, w kobiecie jak w ziemi zamyka się ludzki los. W twórczości Krystyny Lipki-Czajkowskiej Wenus żyje. Jeśli spojrzymy na obrazy zatytułowane Wenus 2014-2015, to zrozumiemy, że kobieta wraz z upływem czasu wraca ze swojego ulotnego piękna, ze swej codzienności do tej niemal archaicznej, mitycznej, uniwersalnej pramatki, którą zawsze – i to jest niezwykły paradoks i głębia tego malarstwa – ma w sobie. Wenus Malarki są bez twarzy, są pisane czerwienią i błękitem, a więc życiem i chłodem (błękit i czerwień obrazują temperaturę malarstwa Artystki), dlatego na jednym z obrazów kobiecość waży się z doskonałością. Częsty motyw koła, kropki, oka, czegoś okrągłego, jakby dla pokazania samego procesu zmagania się z tym, co nieuchronne, ze względu na co tracimy złudzenie, że jesteśmy nieśmiertelnymi bogami, bo nasza cielesność jest jedynie refrenem przemijania, a tym samym praw, które nią rządzą. Rita (lat 7) mówi o obrazie, na którym widzimy Wenus i czerwone małe koło: „Pani waży się z piłeczką.” Słowem kluczowym jest tutaj słowo „waży się” – obraz jest dramatyczny, jest raportem o tym, jak rozpada się kobiecość pozorowana, by odnaleźć drogę do siebie sytej obecnością, ale w jakiś sposób już zawsze niedoskonałej.

Wystawa prezentuje dzieła tworzone w domu, który jest ograniczeniem i rozszerzeniem procesu twórczego, intymność tego malarstwa jest zatem wielowymiarowa. Rita jeszcze nie widzi Wenus, Autorka natomiast już żyje w jej cieniu, Wenus się zbliża, gdyż ciało kobiece brzemienne jest Wenus, dlatego Wenus się dopełni istniejąc jako całość – i tu kolejny obraz, w którym Wenus przybiera bardziej ludzki kształt, brakuje tylko twarzy – no name staje się lustrem, w którym odbija się być może twarz osoby oglądającej obraz. Czerwień wypełnia postać, życie jest jej treścią. To wszystko dzieje się w jakiejś przestrzeni, pozostaje w ruchu, dlatego tak ważne w tych obrazach są linie, które niczym okręgi na wodzie rozchodzą się w różne strony, czyniąc z kobiecości proces bezwzględnie rozpadającej się przygodności. Proste figury geometryczne obecne w tle Wenus zdają się być znakami wodnymi niezmiennych praw tego świata. Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska nazwała swe obrazy Wenus 2014-2015, a więc są to obrazy najnowsze, choć odnoszą się do uniwersalnych porządków myślenia. Malarka mówi o swoich Wenus: „Baby”. Bo „Baba” to ktoś, kto pojawia się w baśniach, w opowieściach, bo „Baba”, to ktoś, kogo ciało traci swoje kontury, gdzie różnice między brzuchem i biustem zacierają się, podobnie jak między barkiem i biodrem.

Współcześnie w kulturze zachodniej kobiety wciąż traktuje się jak słodkie przedmioty, które mają się podobać, mają być atrakcyjne, mają być stałym prologiem, jeśli nawet nie do prokreacji, to przynajmniej do kopulacji. Malarka nie uprawia publicystyki, choć wiele poruszanych przez nią problemów wpisać można w nurty polskiej sztuki krytycznej oraz feministycznej. Autorka swoimi obrazami rozprawia o ontologii kobiecości, której istotą jest Baba, ukryta pod powierzchnią tego, co ulotne, przemijalne. Współcześnie kobieta jako „słodki przedmiot” martwi się przecież, że przestanie być atrakcyjna – tu jakaś zmarszczka, a tu jakaś fałdka, społeczne wzorce ideału ulegają odkształceniu. Kobieta, która przegląda się w zewnętrzności, zawsze skazana jest na niepokój, zawsze skazana jest na doraźność, zawsze traktuje siebie jako winną własnej przemijalności, a przecież może być inaczej, kobieta może być ziemią, życiem, które odkrywa w sobie to, co nieuchronne, to, co konieczne i istotne, a przez to trwałe i mitycznie niewinne, odkrywa siebie jako prawo fizyczne. Taka kobieta jest wolna od złudzeń, już nic nie musi, staje się Babą, staje się Wenus. Baba nie musi spełniać żadnej narzucanej jej roli, nie musi, jak mówi Malarka, „za niczym gonić”. Baba w kobiecie jest pozytywną siłą afirmacji tego, co nieuchronne, a co zawsze wyświetla się na ekranie ciała w postaci przemijania. Baba uzmysławia kobiecie, że jest częścią kosmosu, tego kosmosu, który poznają fizycy, astronomowie, matematycy, geologowie, chemicy, geografowie oraz poeci.

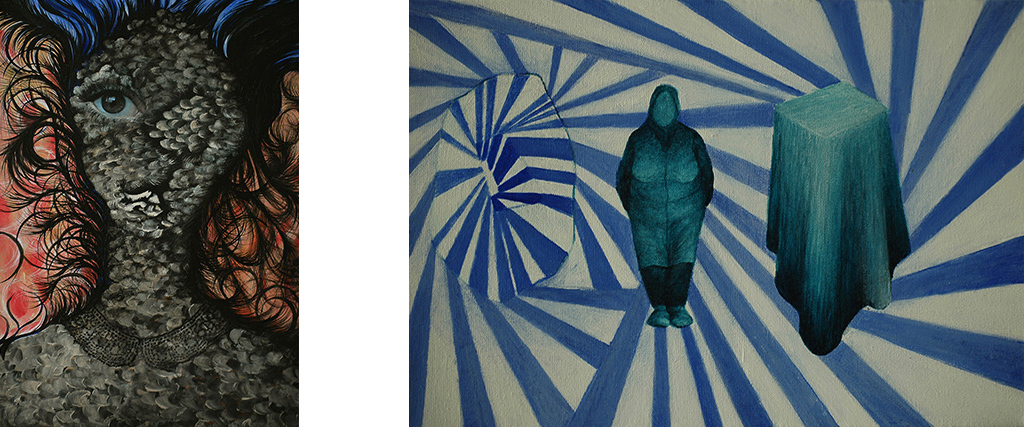

Jak pamiętamy ciała naszych babć, matek, sąsiadek, przyjaciółek? Czy pamiętamy, jak czas wydobywał z nich Baby? W obrazie z 2012 roku zatytułowanym Perspektywa widzimy postać kobiety (domyślamy się, że starej), nakryty czymś stolik oraz schodzące się w jednym miejscu linie niebieskie i białe. Los kobiety – sieć pajęcza przyczyn i skutków, to jedno o nim wiemy, choć go nie znamy, dlatego nakryty czymś stolik ukrywa jakby prawdę, która z powodu swej nieuchronności wydaje się być oczywista, ale wcale nie oznacza to, że jest zrozumiała ani tym bardziej akceptowalna. Nieuchronność jest linią papilarną losu, który upada w ciało kobiety, czyli w świat, z którego nie ma ucieczki, a bycie w nim, to bycie na jego obiektywnych, naturalnych prawach. Baba zmierza do siebie. Współcześnie dla wielu kobiet Baba jest problemem estetycznym, lecz egzystencjalnie wciąż jest kokonem spełnień i niespełnień, oczekiwań oraz rozczarowań, jakby stawanie się Babą wydobywało z kobiety jej lęk przed niewidzialnością, anonimowością, starością.

W perspektywie zbieżnej dalekie obiekty są proporcjonalnie mniejsze w porównaniu z tymi, które znajdują się bliżej. Autorka jednak odwraca w obrazie perspektywę. Odwrócona perspektywa konotuje początek nowego istnienia, mały wybuch życia wikłającego się w ciało, a więc w przemijanie; początek życia kogoś, kto jeszcze nie odkrył w sobie Baby – stolik jest nakryty, lecz prawdy ominąć się nie da, prawda jest do odkrycia. Na obrazie jest jeszcze Baba, czyli nieustanna zmienność tego, co stałe. Jakby twórczość Krystyny Lipki-Czajkowskiej mówiła: z Baby powstałaś i w Babę się obrócisz.

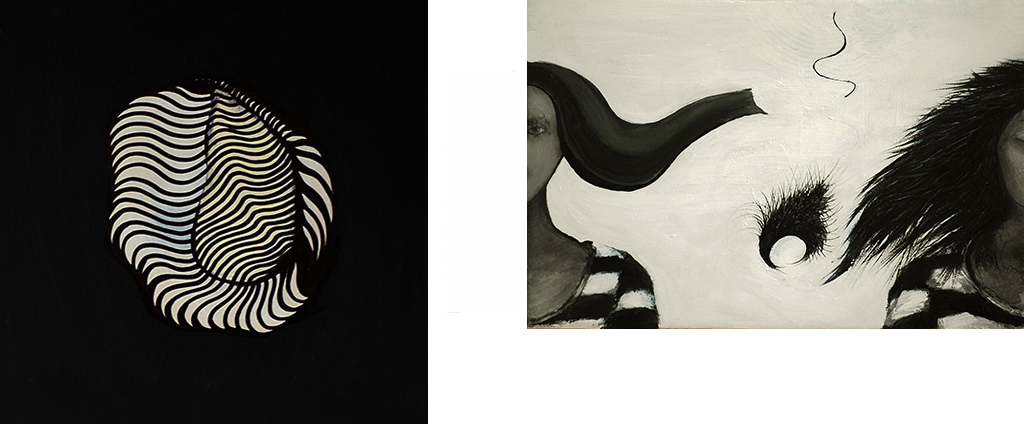

W obrazach pojawia się również daimonion, który jednak nie istnieje w otoczeniu Baby, lecz zamiast niej. Autoportret z kobietą z 2013 roku jest przepisanym daimonionem. W tradycji religii monoteistycznych daimonion oznaczał coś nieczystego, coś, co nie jest na właściwym miejscu, coś nieuporządkowanego, co chce całkowicie zawładnąć duszą. W Autoportrecie z kobietą jedno oko jest już zamknięte, jakby zarośnięte, drugie pozostaje otwarte. Dusza z zamkniętymi oczyma będzie martwa, daimonion weźmie ją we władanie. Otwarte oko w swojej ostrości, naiwności i czystości patrzy na nas, jakby broniąc duszy kobiety przed totalnym zwycięstwem daimoniona. Ciekawe jest, że spojrzenie kobiety z obrazu krzyżuje się ze spojrzeniem odbiorcy. Rozalia (lat 10) mówi o obrazach swej matki: „obrazy patrzą się i zajmują miejsce”. W spojrzeniu postaci z Autoportretu jest imperatyw: patrz na mnie, patrz, chroń mnie przed daimonionem.

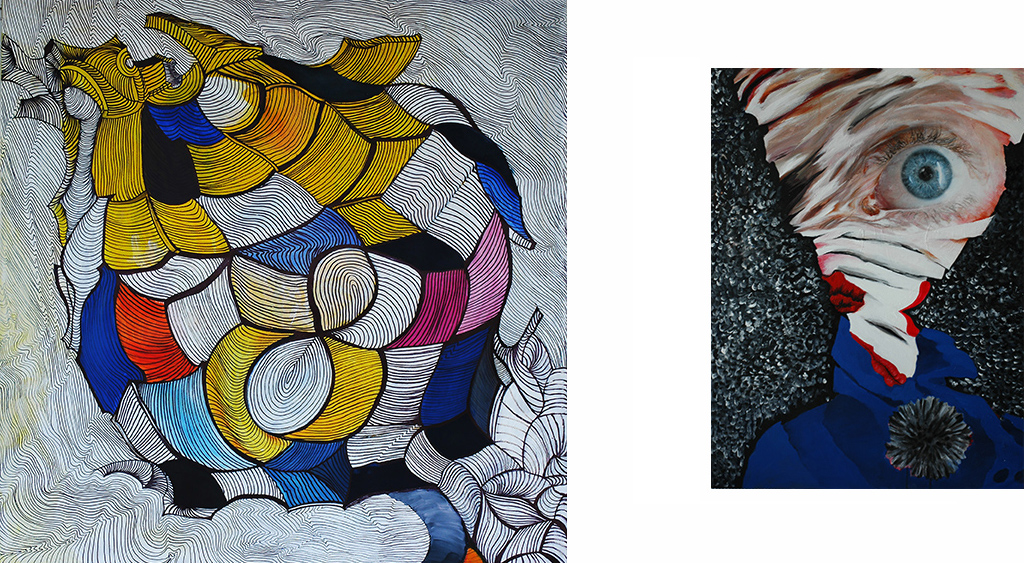

Imperatyw spojrzenia uwalnia się interpretacyjnie w obrazie Bez tytułu z 2015 roku, jedynym obrazie, w którym pojawia się barwa żółta, niemal słoneczna. Obraz ten w płaszczyźnie odwzorowuje jednocześnie wiele wymiarów, jest rzeźbą dla oka, które chce patrzeć, które chce dojrzeć w przestrzeni ruch, bo przestrzeń bez ruchu to przestrzeń zawłaszczona przez demoniczne spojrzenie. Daimonion nosi rękawiczki, podkłada w miejsce czerwonej kuli czarną, jest potwarzą Baby, przebiera się w jej intymność, gdy z ludzkich włosów układa twarz. Mówię o serii obrazów zatytułowanych Po TWARZ (2013-2015).

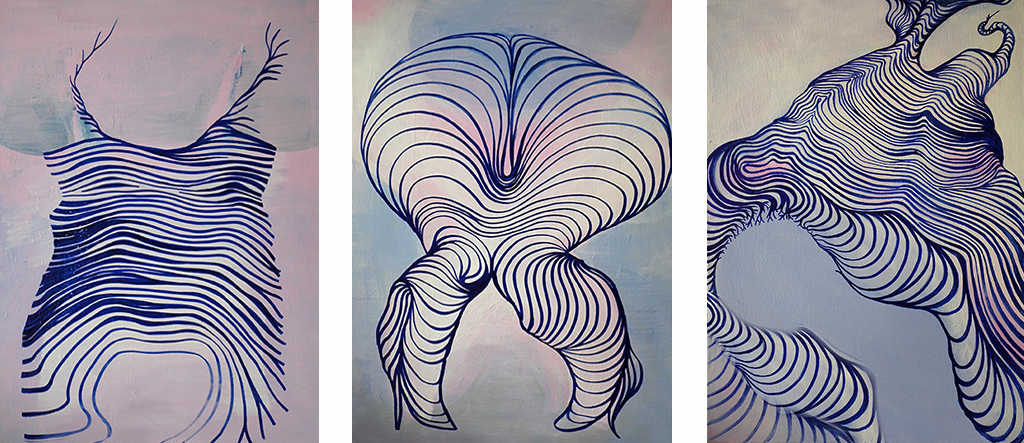

W trzech obrazach Bez tytułu widzimy odwrócony porządek zależności – to w rzeczach odciśnięte jest ciało, widzimy odciśnięte kształty piersi, brzucha, ramion. Zazwyczaj, gdy zbyt długo spoczywamy w jednej pozycji, to na naszym ciele pozostają ślady noszonych przez nas rzeczy. W malarstwie Krystyny Lipki-Czajkowskiej jest odwrotnie. To w rzeczach odciska się ciało kobiety, jednakże rzeczy, choć pełne odcisków po ciele, są efemeryczne, wręcz metafizyczne. Wyrzucamy ubrania, gdy są znoszone, w tych trzech obrazach to ciała są znoszone, dlatego rzeczy po nich jeszcze „pamiętają” ich formę i ciężar, ale już jakby pozbyły się swego balastu. W dynamice linii białych i niebieskich kryje się ironia, jakby rzeczy pamiętały jeszcze o podstawowych potrzebach ciała kobiety, o jej fizjologii, lecz to wszystko przypomina pusty skład po czymś, co już się zużyło, co przeminęło. W tych obrazach ciało jest świadkiem tego, jak nieuchronnie „wypada się” z życia. Zostaje z niego i tak niewiele – kilka odcisków na rzeczach, które są już trochę nie z tego świata.

Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska maluje córkami, maluje codziennością, mężem, maluje nadzieją, intymnością, ale też smutkiem, lękiem i niepokojem. Te wszystkie stany skupienia jej malarstwa są barwami, które czynią z jej twórczości opowieść niezwykłą, niedającą się zredukować do naiwnych stwierdzeń typu „podoba się”, „nie podoba się”. Nieuchronność jest częścią egzystencji zarówno wtedy, gdy akceptujemy ją – znajdując w niej jakiś sens, jak i wtedy, gdy ją negujemy, wierząc, że można od niej uciec, co przecież nie jest możliwe, bo przychodzi to, co przyjść i tak musi.

Marek Kaźmierczak

Instytut Kultury Europejskiej UAM w Gnieźnie

—

The (in)evitability of maturity

The painting of Krystyna Likpa-Czajkowska is nonintrusive, far from megalomania, exhibitionism, literality, illusion, and following trends. The author redraws images from originals, which, as she claims, ‘reside’ inside her. She is a painter who builds her relation with the painting during its creation, and also afte it has been immortalised on canvas, sometimes even on tips. The author ‘likes to be surprised by the painting’, she likes when ‘the painting leads her’, when ‘it detaches from her’, and finally ‘when it leaves her in peace’. The painter treats her paintings like a medium, which connects us with the truth about her femininity, sometimes even her ‘womanliness’, with the daimonic reality, with the geometry of body and soul, with the space of her intimacy and the intimacy of her space. The painter always waits for the moment when the painting ‘detaches’ from her, then for a moment life becomes eternal.

I wrote that the artist paints redrawing the originals that reside inside her. These originals are deposited there by everyday life, art, grandma stories, culture, motherhood, sexuality, femininity, sensitivity, corporality, and finally, by daimons. In my opinion the resemblance to the tradition of iconography is visible in the way the painter renders the object on a plane perceived from many different perspectives. The resemblance is also visible in how she inverts the painter’s perspective, in how she layers colours, in how she employs their symbolism, and in how she builds hierarchies, ordering the importance of people and things. Those are not simple inspirations stemming from the content, those are hardly inspirations at all. Those are interpretational frames with which one can enter the realm of her painting and her corporality constantly consumed by time. In her paintings Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska creates iconographies of everyday life, in which femininity plays a role of the sacred, falling apart into the profane of matters, tasks, duties, roles, functions, fashions, needs, and someone else’s expectations. This falling apart is need so that Maturity can be born in the woman. There is a story from her life, which confirms the above.

A phone call, similar to many other phone calls we have in life. Someone asks ‘Are you painting? I will call you when they are dry, then… what colour?’ ‘Blue.’ – the painter answers.

‘Blue?’ – surprise clear in the other persons’ voice. It is obvious: with a house, a family, children, there can be no place for anything else but painting nails. This conversation explains a lot. Firstly, that with the imposition of typical social roles on her, the woman’s desire for emancipation is stifled. Secondly, that usually multidimensionality is not expected of a woman when she realises obvious tasks, then, a fraction of her personality must do in place of the entirety of it. It must be said that the artist transfers some of her paintings on tips, facing their artificiality, the semblence of their durability, and also all the things in modern culture that they symbolise. Painting tips may become a creative work, according to the artist “Painting is feminine”.

In European culture the woman body for ages has been an object of adoration, praise and condemnation. The woman is life, but also death, because her body becomes a link between our existence and inexistence; we are born from it and consequently we later die. The woman is a circle in which the time of human existence is confined. Maybe that’s why, as Karl S. Guthke writes in his book The Gender of Death, similarities between the woman body and the earth were being found thousands of years ago, the woman gives life incorporating it in the order of life which death at its end. That correlation is visible in the example of Venus of Villendorf – the woman is fertile just like the earth, the woman, just like the earth, encompasses human fate. Through the works of Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska, we can understand that Venus is alive. If we look at the paintings titled Wenus 2014-2015 (Venuses 2014-2015), we will understand that as time goes by the woman returns from her passing beauty, from her everydayness to that almost archaic, universal foremother, who she always has inside, and this is the paradox and the depth of Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska’s painting.

The Venuses of the painter don’t have faces, they are painted with red and azure, hence with life and coldness (azure and red represent the temperature of the Artist’s painting) that’s why on one of the artist’s paintings femininity is balanced with perfection. The frequent theme of a circle, a dot, an eye, something round, as if to merely show the process of struggling with what is inevitable, of struggling with what causes us to lose the illusion that we are immortal gods. We lose the illusion because our corporality is only the chorus of our evanescence and the rights ruling it. ‘The lady is balancing with the ball’ that’s what Rita (7 years old) says about the painting on which we see Venus and a small red circle. The key phrase here is: ‘balancing with’ – the painting is dramatic, it is a report on the decay of apparent femininity, which leads to finding satiation with presence, but in some way for ever imperfect.

The exhibition consists of works created at home, which is both a limitation and an extention of the creative process, the intimacy of the artists’s painting is thus multidimensional. Rita does not see Venus yet, the author on the other hand already lives in her shadow, Venus is coming, because the woman’s body is burdened with Venus. Hence Venus will fulfill her destiny and will exists in her entirety – here as an example yet another painting in which Venus takes on a different, more human shape, the face is the only thing lacking – no name becomes a mirror, and perhaps the face of the person looking at the painting is reflected in it. Red is filling the figure on the paiting, life is its content, all this is happening in some space, keeps moving, that is why lines, that are like ripples on the water, which by moving in different directions make the femininity an inevitable process of randomness that is falling apart. Simple geometric figures in the background of Venus seem to be the watermarks of the unchanging laws of this world. Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska called her paintings Venuses 2014-2015, so they are the newest paintings, although they refer to the timeless turn of mind. The painter calls her Venuses “mature”. Because “the mature woman” is someone that appears in fairytales, stories, someone whose body looses its contours, with the differences between a belly and a bosom becoming blurred, similarly to those between a shoulder and a hip.

Nowadays, in western culture women are still treated like sweet things, that should be pleasing to the eye, attractive, be a constant prologue, if not to procreation then at least to copulation. The painter is not a publicist, although many of the problems she touches upon can be inscribe in the Polish currents of critical art and feminist art. With her paintings the author discusses the ontology of femininity with the mature woman being its essence, hidden underneath of what is ephemeral, passing. Nowadays, the woman as a “sweet thing” worries, mind you, that she will stop being attractive – one wrinkle here, another crinkle there-society’s ideals are being distorted. The woman who sees herself in the mirror of superficiality is always doomed to be anxious, always bound to the interim, always treats herself as the culprit of her evanescence, however, it does not have to be like that. The woman can be the earth, life, that discovers in itself, what is inevitable, what is necessary and of essence and thus lasting and mythically innocent, finally discovering itself as a law of physics. A woman like that is free from illusions, she is not bound anymore, she becomes the mature woman, she becomes Venus. The mature woman does not have to conform to a role imposed on her, does not have to, as the painter says, “chase anything”. Maturity in the woman is a positive force of what is inevitable, what is always displayed on the screen of the body in the form of evanescence. Maturity makes the woman realise that she is a part of the cosmos, the cosmos that will be known to physicists, astronomers, mathematicians, geologists, chemists, geographers, and poets.

How do we remember the bodies of our grandmas, mothers, neighbours, friends? Do we remember how time extracted the maturity from them? In the painting from 2002 titled ‘Perspektywa’ ( Perspective) we see a silhouette of a woman ( we are guessing it’s an old woman) a table covered with something and blue and white lines meeting in one point. The woman’s fate – a spider web of causes and effects, that’s the one thing we know about it , although we do not know it, that’s why the table covered with something hides some kind of truth, which because of it’s inevitability seems to be obvious, but that does not mean, that it is understandable or acceptable for that matter. Inevitability is the fingerprint of fate, which falls into the woman’s body, and consequently into the world, from which there is no escape and being in it means having to respect its objective, natural laws. The mature woman is on the way to her destiny. In the present the mature woman is an aesthetic for many people, but existentially it is still a cocoon of fulfillment and unfulfillment, expectations and disappointments, it is as if maturing pulled out the fear of being invisible, anonymous and old from the woman. In linear perspectice the far away objects are proportionally smaller than those that are closer. The artist, however, inverts the perspective in the painting. The inverted perspective connotes the beginning of a new being, a small outburst of life which is entangling itself in the body, hence in evanescence; the beginning of life of a woman that has not discovered maturity in herself yet – the table is covered, but the truth cannot be avoided, the truth waits to be uncovered. In the painting the mature woman, thus the constant variability of what is, invariable. As if the works of Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska were saying: you were born out of maturity and you will return to maturity.

There’s also a daimon in the paintings, however it is not in the surroundings of the mature woman it is there instead of her. Autoportret z kobietą (Self-portrait with the woman) from 2013 is a daimon that has been redrawn. In the tradition of monotheistic religions daimon meant something impure, something that is not in the right place, something unordered, that wants to completely take over the soul. In Autoportret z kobietą one eye has already closed as if it had been overgrown, the other eye remains open. A soul with closed eyes will be dead, the daimon will take control over her. The opened eye looks at as with its sharpness, naivety and pureness looks at as, as if defending the woman’s soul from the total triumph of the daimon. Interestingly, the look of the woman from the painting crosses with that of the looker. Rozalia (10 years old) says this about her mother’s paintings: ‘the paintings look and take up space’. In the look of the figure from Autoportret there is an imperative: look at me, look, protect me from the daimon.

The imperative of that look becomes interpretatively free in ‘Bez tytułu’ (‘No title’) from 2015, the only painting in which yellow colour, in almost sunny tone, appears. That painting simultaneously shows multiple dimensions on a plane, it is a sculpture for the eye, which wants to look, which wants to see movement in space, because space without movement is a space appropriated by a demonic look. The daimon wears gloves, puts a black ball in place of the red one, it is an impostor of the mature woman, it dons her intimacy when he puts together a face made from human hair. I am talking about a series of paintings titled ‘Po TWARZ’ (2013-2015) (The title has double meaning because TWARZ means ‘a face’ in Polish and potwarz means ‘an insult’ [translators’ comment]). In the three paintings we can see an inverted order of dependence – a body is imprinted in clothes, we see the imprinted shapes of breasts, a belly, and shoulders. Usually when we remain in one position for too long, the clothes we are wearing leave marks on our skin. In Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska’s painting it is the other way round. It is the woman’s body that leaves its marks on clothes, but clothes, despite being riddled with marks and dents are ephemeral, even metaphysical. We throw out clothes when they wear out, in those three paintings the bodies are the ones that have worn out, that’s why the clothes they used to wear still ‘remember’ their form and weight, however they somehow have gotten rid of their burden. Irony hides in the dynamic of the blue and white lines as if the clothes still remembered the basic needs of the woman body, her physiology, but all this resembles an empty store of something that has worn out, something that has passed. In those paintings the body is the witness of the inevitable ‘falling out’ from life. Not much remains of it – a few marks on clothes, which are already a bit out of this world.

Krystyna Lipka-Czajkowska paints using her daughters, everydayness, husband, hope, intimacy, but also using her sorrow, fear, and aniety. All these matters of state of her painting are colours, which makes her art an unsual story unusual, one that refuses to be defined by simple statements like ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it’. Inevitability is a part of existence, both when we accept it – finding some sens in it – but also when we negate it, believing that we can escape from it, which is actually impossible, because what must come always comes.

Marek Kaźmierczak

Instytut Kultury Europejskiej UAM w Gnieźnie